3. Effects of Hyperoxia

Breathing too much oxygen (this is called hyperoxia) can intoxicate us and cause some health problems.

How does it work? Oxygen releases tiny bombs called free radicals in our bodies. It always does this, even when we are on the surface, where we eliminate them without much problem. But when we breathe too much oxygen for too long or at high pressure, free radicals accumulate and can damage our cells.

Which organs are affected? Mainly the lungs and the nervous system.

- Lungs: If we breathe oxygen at high pressure for a long time, it can irritate our lungs and cause breathing problems, resulting in what is called Lorraine-Smith syndrome or chronic hyperoxia. Symptoms of chronic hyperoxia include itching, burning, and chest pain, as if you had swallowed a cactus. Then, dry cough, chest pain, and difficulty breathing. If you don’t stop, things get worse: convulsions, loss of consciousness.

- Brain: In divers who go to great depths, excess oxygen can affect the brain and cause dizziness, convulsions, and loss of consciousness, known as acute hyperoxia (Paul Bert syndrome). Symptoms: Tachycardia, tremors, nausea, vomiting, vertigo, ringing in the ears, nervousness, irritability, blurred vision, and… convulsions! It’s very dangerous, and you need to act as soon as symptoms appear.

4. Treatment of Hyperoxia

The Lorraine-Smith syndrome or pulmonary hyperoxia can be prevented by not exceeding the safety doses indicated for each gas. If we ignore the guidelines and lung damage occurs, a doctor will have to intervene. DAN describes pulmonary hyperoxia as similar to the flu, while other sources mention a sensation similar to asthma. However, everyone agrees that in rare cases it results in permanent damage.

But how do you act in the face of acute hyperoxia (great depths)?

A diver with hyperoxia may realize their body is intoxicated and ascend, but if they don’t recognize the symptoms, they will depend entirely on their partner. To act appropriately, it is essential to know the different stages of the intoxication process.

Phase 1: Prodromal. You might not notice it because the symptoms are very mild or because they don’t occur.

Symptoms: Tachycardia, tremors, nausea, vomiting, vertigo, ringing, irritability, and tunnel vision.

Solution: Ascend NOW! ⬆️ Up, up, as the oxygen is getting to your head.

If not detected, the diver will suffer a convulsive crisis.

Phase 1: Prodromal. You might not even notice it because the symptoms are very mild or because it might not happen at all.

Symptoms: Tachycardia, tremors, nausea, vomiting, vertigo, ringing in the ears, irritability, and tunnel vision.

Solution: Ascend NOW! ⬆️ Up, up, the oxygen is getting to your head.

If we don’t detect it, the diver will suffer a convulsive crisis, which has 3 more phases.

Phase 2: Tonic. (less than 1 minute)

Symptoms: Faints, becomes rigid, and stops breathing.

Phase 3: Clonic. (2 or 3 minutes)

Symptoms: Convulsions and relaxation of sphincters.

Phase 4: Post-crisis depression.

Symptoms: The diver is sleepy and disoriented, with no memory of the event.

Action:

In 2012, Dr. Simon Mitchell signed a document titled “Recommendations for rescue of a submerged unresponsive compressed-gas diver,” which compiled the action recommendations from prestigious organizations such as the Diving Committee of the Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society, Divers Alert Network (DAN), the University of Washington, the University of California, and the U.S. Navy Experimental Diving Unit, among others.

His summarized recommendation was as follows:

- Convulsing WITHOUT mouthpiece: Ascend NOW!

- Convulsing WITH mouthpiece: Hold them, and when they stop convulsing, ascend.

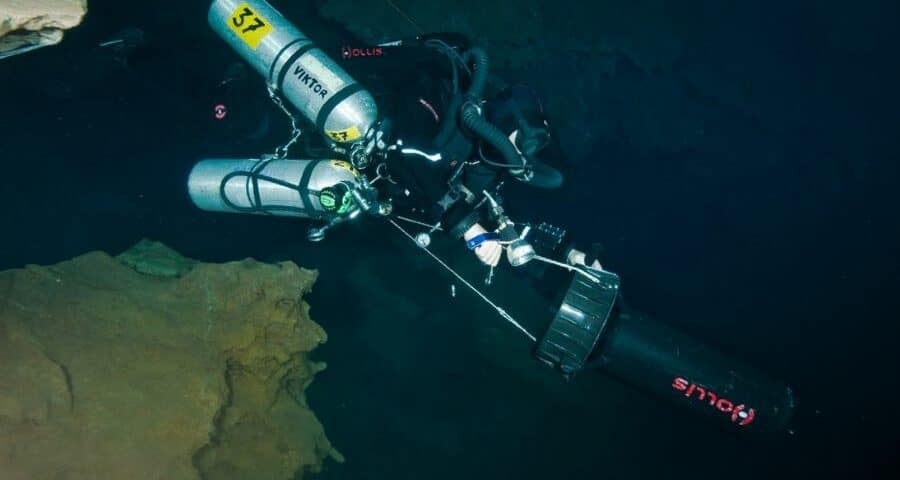

However, recently Divers Alert Network (DAN) has published new articles regarding the treatment of hyperoxia during diving, recommending an ascent even if the mouthpiece is in place. (In this case, it explains the steps with a rebreather diver, but they can be applied to open system diving) We summarize the steps below:

- Position yourself behind the diver.

- Release the weights: Remove their weight belt unless they are wearing a dry suit. In that case, leave it on to avoid them flipping face down upon reaching the surface.

- Mouthpiece: If the mouthpiece is in place, don’t touch it. If it falls out, don’t try to put it back, just ensure it is in the surface position.

- Hold the diver by the chest, above the regulator, or between the regulator and their body. If you can’t control them this way, use the best method at hand.

- Controlled ascent: Ascend slowly to the surface, maintaining slight pressure on the diver’s chest to help them exhale.

- Extra buoyancy: If you need more buoyancy, activate the diver’s BCD, but not yours, and don’t remove your weight belt.

- On the surface: Once on the surface, if you haven’t already, inflate the diver’s BCD.

- Remove the mouthpiece: Once on the surface, remove the diver’s mouthpiece and switch the valve to the surface position.

- Emergency signal: Alert everyone! Make the emergency signal to get help.

- Clear the airway: Tilt the diver’s head back to open their airway and ensure they are breathing. If they are not, a trained diver can initiate mouth-to-mouth resuscitation.

- Monitoring and decompression: Monitor the diver for signs of decompression sickness.